TV FORMAT FUNDAMENTALS: EPISODIC DRAMA

Welcome back to TV Formatting Fundamentals – the blog series where we take a deep dive into the evolution and act structure of various TV formats.

This week we’ll look at Episodic Drama.

Over the years, television has evolved to be more serialized than episodic, but it’s helpful to understand both types of storytelling. When we talk about episodic television, we refer to shows like Scooby-Doo, where a character or group of characters is presented with (and fully solves) a new case in each episode.

The recent decline in episodic drama series can be tied to the rise of streaming platforms where episodes tend to drop all at once rather than airing week-to-week.

Episodes of serialized television are more like chapters in a book. Each episode builds upon the previous one and is a slice of a much larger story (think: LOST, Game of Thrones, Stranger Things… even the Marvel Cinematic Universe, etc.). Serialized TV is made for bingeing because the spectator simply hops to the next part of the big, season-long story.

By contrast, a viewer can understand an episode of Star Trek, Law & Order, Seinfeld (and the comedies we discussed in last week’s post about multi-cam sitcoms) etc. without having seen the previous episodes. Whether comedy or drama, each installment of an episodic show uses the same characters, yet is self-contained. For this reason, these shows tend to do well in syndication.

Because they require a new case, situation, or monster each week, episodic dramas tend to be workplace shows. They’re about detectives, doctors, lawyers, vigilantes, ghostbusters…. professions which operate on a “case-by-case” basis.

Episodic drama on television has origins in police procedurals, which are an offshoot of radio detective shows. Dragnet is an early and prominent example.

Beginning as a radio show in 1949, Dragnet became so successful it was developed into a TV series in 1951. Airing on TV, its format didn’t change much. Each episode finds Detective Joe Friday chasing down a new perp and using lots of technical police jargon along the way. Dragnet predates formal act structure, but the scripts do specify three commercial breaks. In fact, right before the closing commercial, the show leaves the viewer with the evidence presented to a jury, but the viewer must return after the commercial to learn the jury’s final verdict.

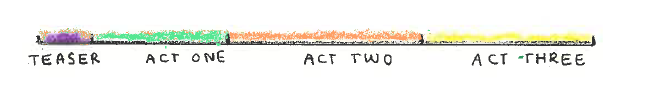

Also co-created by Dragnet writer/producer/star Jack Webb, Adam-12 is another early procedural full of realism and technical mundanity. Two police officers ride around and work to solve a new crime each week. With Adam-12 and other shows of the 1960s, the formatting evolved slightly. The Adam-12 officers, Malloy and Reed, are presented with a new case or situation in the show’s teaser, they then make progress and face setbacks across three acts. In the final act, they solve the case or apprehend the perp they were chasing.

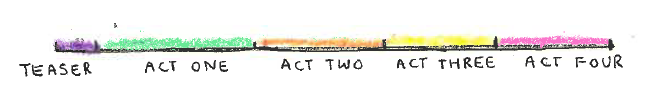

Later, episodic/procedural dramas evolved from the Adam-12 style teaser and three acts to simply four acts. A dead body almost always appears in the first act of an episode of Murder, She Wrote; new suspects and red herrings come to the fore in acts two and three, then Jessica Fletcher solves the case in act four. Other examples with four-act structure include: Cagney & Lacey, The Practice, St. Elsewhere, Hill Street Blues.

Kirk, Spock and the Enterprise crew are presented with a new intergalactic situation in a short teaser, then face complications in acts one, two and three and some kind of resolution in act four on Star Trek.

Adding a teaser to the four act structure became especially fashionable in the 1990s and early 2000s. Law & Order, The X-Files, ER and Buffy the Vampire Slayer all use this type of formatting. The new case or situation is presented in the teaser and characters spend the next four acts, working to cure the patient, slay the monster or find justice. During this era, episodic dramas became a bit more complex and started taking on more serialized elements. Buffy is a great example of this. There’s a monster of the week that she must fight, but there’s also an overarching monster of the season, causing the episodes to build on each other in interesting ways.

In the early days of episodic television, characters were just damn good at both their jobs and family lives. They rarely messed-up or had to deal with their own issues or trauma. After all, it’s hard to have new stories or cases each week, if the emphasis is on the character’s growth and evolution. On Buffy, the titular heroine fights a new monster every week, but that monster is obviously a stand-in for whatever crappy thing she’s going through in her day-to-day teenage life. It’s a smart blend of both episodic and serialized elements.

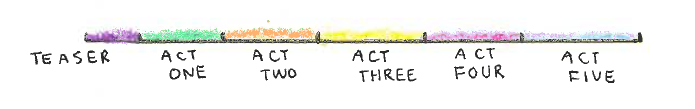

In the mid-2000s, the way viewers consumed television began to change drastically with DVR and streaming. The need for more commercial breaks translated to more act breaks in scripts. See shows like Boston Legal and Medium for a teaser and five-act structure.

Most episodic-leaning dramas on TV today utilize the teaser and five-act structure or they utilize six acts.

In the early days of episodic dramas, a show followed one Joe Friday or Jessica Fletcher around for the duration of the two-to-four-act episode. With more commercial breaks and a more sophisticated viewing audience, today’s six-act episodic dramas are likely to utilize A, B, C and sometimes D stories to fill the full episode.

The idea of balancing multiple plots in one episode might seem a little intimidating, but it’s helpful for a writer working in today’s market to look at six-act structure since it’s the commonly used structure of the day.

Believe it or not, even whilst juggling multiple plots, detective and medical shows still utilize the idea of a monster or a case of the week. With six-act structure, there tends to be more than one case/monster per episode. Act structure and theme play a massive role in giving A, B and C stories a sense of cohesion.

Let’s look at a great episode from season 2 of Grey’s Anatomy.

CASE STUDY:

GREY’S ANATOMY “BREAK ON THROUGH”

Written by Zoanne Clack

This episode has not one, but three surgical intern protagonists: Meredith Grey, Christina Yang and Izzie Stevens. While the episode services ALL of the characters, honing in on these three helps the reader identify the A, B and C plots.

Throughout the early seasons of Grey’s, Meredith is the main character with Christina and Izzie often serving as foils—one competitive and bossy; the other hyper-empathic and nurturing with patients.

ACT ONE

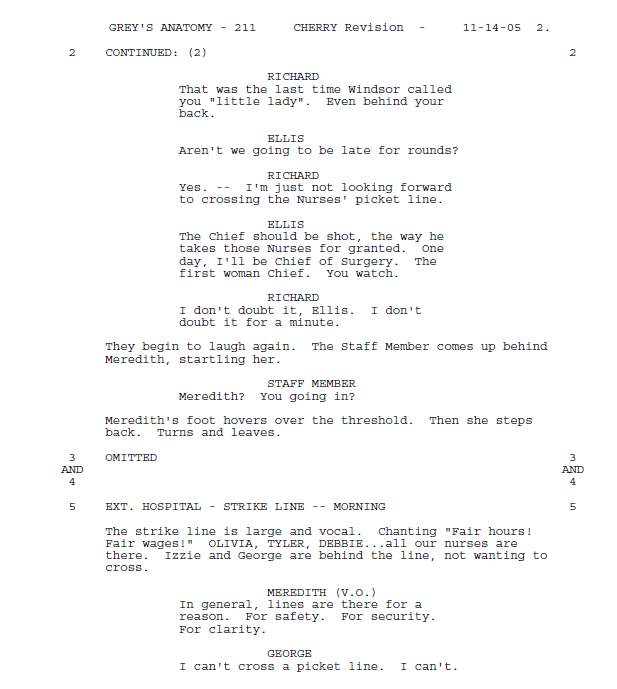

In “Break on Through” each woman is presented with a “patient of the week.” Each patient represents a variation on the episode’s theme, which is introduced through Meredith’s voice-over at the very start: “In surgery, there’s a red line on the floor that marks the point where the hospital goes from being accessible to being off-limits to all but a special few.”

The theme is “crossing a line,” and each case this week will cause each intern—Meredith, Christina, and Izzie—to face a hidden, hard truth about themselves.

In a six-act episodic drama script, think of the first act much like the first 10 pages of a feature screenplay. The characters go from being in their “ordinary world” to being assigned their case, which acts as a catalyst.

The first thing we see is Derek and Addison talking in his airstream.

Then, Meredith goes to visit her mother Ellis, who is suffering from Alzheimer’s in a nursing home. Meredith finds her boss, Chief of Surgery Richard Webber, visiting her mom – and decides not to confront or interrupt them. This is the start of the Meredith / A storyline.

The theme of “line crossing” roars into high gear when Meredith gets to work to find the Seattle Grace nurses have gone on strike and are picketing outside the building. Her fellow interns George, Izzie, Christina and Alex debate whether they should “cross the line” and go into work.

While the others go inside, George stays with the nurses and doesn’t “cross the line.”

On page 3 – We’re reminded that the intern’s resident, Dr. Bailey, has started her maternity leave. The interns are to spend their time being supervised by Dr. Sydney Heron, a ball of pep, which immediately doesn’t sit well with Christina and is the start of her storyline. For our purposes the “B” storyline.

The B storyline continues as Dr. Heron sends Christina and Alex to consult on a patient with a mysterious rash. The patient is a marathon runner who happens to be on her honeymoon. BOOM! Christina is presented with her case this week.

This scene is followed by Meredith’s case of the week: Grace, a woman in her 80s who is having trouble breathing and calling out to someone named “Len.” This is a catalyst.

At the end of act one, George doubles down on his decision to NOT cross the line. He continues to support the nurses.

ACT TWO

At the start of act two, Meredith stays with Grace, who quickly panics and declines. Without the usual help of the nurses who are striking, Meredith doesn’t know anything about the patient and intubates her. She also sees Dr. Webber and mentions seeing her mother, but doesn’t confront him about visiting her.

Meanwhile, Izzie gets assigned a case (the start of the C plot) – helping Dr. Addison Shepherd with a pregnancy in which a mass is growing on the unborn baby’s neck. Izzie helps to explain the surgery needed and relate to the patients. As viewers we get a sense that she has a deeper understanding of this situation than she lets on. It’s juicy writing because we MUST KNOW what’s going on with her and what she’ll do next.

We jump back to the B plot, where Christina, Alex and Dr. Heron learn that what seems like a rash is growing out of control past the lines of a circle that Christina drew on it…

Richard laments the lack of nurse power.

Meredith has an awkward encounter with Derek, who is back with Addison. (The Meredith-Derek relationship is one of the serialized elements of the show.)

Meanwhile, Christina, Alex and Heron learn their patient has Necrotizing Fasciitis – the flesh-eating bacteria – and they have to act FAST.

The striking nurses try to convince George to cross the picket line to go check on their patients.

Back in the A storyline, Meredith’s patient Grace is visited by some friends. Meredith learns the patient was DNR (Do Not Resuscitate), that intubating her was a mistake and she was supposed to let her die. This is a great act out. In the last line, we learn Meredith is in big trouble, so obviously we have to come back after the commercial to see what happens.

ACT THREE

Act three might be seen as the act where the case becomes more personal to the character.

Here, Meredith learns that her intubated patient is a widow and that her daughter lives far away in Oregon. The patient is not unlike Meredith’s own mother.

With their Necrotizing Fasciitis case, Dr. Heron, Christina and Alex operate on their patient. Despite the extremely fast-moving bacteria, Heron argues to try to save the leg. Christina thinks this will jeopardize the patient’s life and advocates for removing the leg, to which Dr. Heron implies she has no compassion.

Both Dr. Shepherds will be able to get help pregnant teen Cheyenne deliver her baby a bit earlier than expected. Izzie stays with Cheyenne after the consultation and wonders if she’s made plans for actually having the baby. Again, Izzie gets more personally involved, but we’re not quite sure why. There’s “something in her face.” The mystery of WHY this is personal to her keeps us watching.

In another intense act-out, Christina goes to Dr. Burke and informs him that her new resident is trying to kill a patient!

ACT FOUR

Act four introduces higher stakes and tough choices.

Dr. Webber comes to assist with Meredith’s patient, making the situation seem all the more close to the one with her mother. Here’s a stake-raiser: if the patient’s daughter makes it down to the hospital and confirms that her mother is “Do Not Resuscitate” Meredith will have to pull the plug or “kill” her patient.

Meanwhile, Dr. Burke – on behalf of his girlfriend, Christina – goes to check on Dr. Heron to make sure she’s not killing any patients. The normally peppy Dr. Heron sternly calls Christina out for lacking in compassion…

A, B and C plots all intersect when Meredith, Christina, and Izzie go to lament that situations they’re in. We’re still wondering what’s going on with Izzie. In beautiful counterpoint, the nurses celebrate George for not technically crossing the picket line, but nonetheless helping their patients.

Izzie pays an after-hours visit to her pregnant patient Cheyenne, revealing that she is from the same trailer park in Chehalis. In another powerful act-out, Izzie reveals that she has a daughter. We’re definitely coming back after the commercial break to find out more….!

ACT FIVE

Act five is the act with the major setbacks, where our principal characters find themselves in the deepest trouble.

Izzie suggests to Cheyenne that keeping and raising the baby aren’t necessarily her only option.

Burke gets real with Christina about asking him to question another surgeon in her own O.R., which puts strain on their relationship.

George meets with some of the doctors to pass on information from the nurses about what their patients need. In the same scene, Meredith is met by Alice, her patient’s daughter AND Izzie is confronted by her patient’s mother and chastised for putting the idea of giving her baby up for adoption into her head.

Meredith goes with Dr. Webber and Alice to remove the patient Grace’s breathing tube.

Dr. Heron has saved the bacteria-ridden leg and looks for an apology from Christina.

At the end of the fifth act, Meredith finally tells Dr. Webber she saw him with her mother. He asks if she would like him to stop going but she doesn’t give him an answer.

ACT SIX

We arrive at act six, which is the final strain and climax of the episode.

Meredith’s patient, Grace, passes away. Look at writer Zoanne Clack’s description here: “… Grace, gasping for breath. It’s terrible and beautiful and ethereal and painful.” That’s some involving description.

Meredith runs out of the room, sick and hyperventilating. This hits just a little too close to home. Derek (who we’ll remind you is happily back with Addison), finds her in a supply closet and helps her catch her breath. They don’t kiss.

Dr. Burke forces a reluctant Christina to apologize to Dr. Heron, who wants to hug it out.

Dr. Webber, the Chief, decides to meet the nurses’ demands and bring them back because clearly they can’t do their work effectively without them.

Izzie helps Cheyenne after the birth of her daughter and processes feeling about her own daughter that maybe she hasn’t really processed before.

George goes back to work, having managed to stay behind the picket line.

Derek and Addison decide they’ll build a house.

The final scene finds Izzie and Meredith crawling into bed with George. The characters have gone through a whirlwind of emotions with their patients, but at this moment, refrain from sharing their deepest secrets with each other. Rather, they just lay there.

And there you have it.

The case or the patient or the monster of the week has your character(s) dealing with emotions that they’re afraid to talk about with their closest friends and colleagues. The episode helps to draw them out.

Food for thought next time you sit down and write.

Until next time, happy scribbling!